At least 34 people have died and more than 1,600 have fallen ill in the vaping-related lung illness outbreak that’s swept across the country since March. And months into their investigation, disease detectives at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say they still don’t know exactly what’s causing the severe shortness of breath and chest pain that’s landed people in hospitals.

One class of vaping product, however, has consistently been implicated in the illnesses: unregulated and unlicensed cartridges that contain THC, the main psychoactive chemical in cannabis.

According to the latest CDC data, 78 percent of the 849 patients who have provided information on their vaping habits reported using THC-containing products. Though the agency isn’t tracking whether people were using legal or black market sources to vape, the data we have from states suggests it’s overwhelmingly illicit, pre-filled THC vape cartridges making people sick.

On Tuesday, the CDC’s Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report published a study from Utah showing 92 percent of patients interviewed reported vaping THC — and mostly from pre-filled cartridges — before falling ill. The vape products, the CDC said, “were acquired from informal sources such as friends or illicit in-person and online dealers.” Dank Vapes, a popular black-market manufacturer, was the most commonly used brand. Research in Illinois and Wisconsin shows the same pattern. And in New York, the state Department of Health commissioner has said the vast majority of the 125 cases there have been linked to black market THC cartridges.

As this data has emerged, the outbreak is looking less like a story about general vaping risks and more about the harms of vaping certain THC products. It’s also a reminder that the way people use THC is shifting.

“What’s changed is that people used to vape dried herb and now you have more vaping of preprocessed manufactured oils, which involve different ingredients,” said David Hammond, a public health researcher at the University of Waterloo in Ontario who studies the e-cigarette and THC vape markets in Canada and the US.

Yet health regulators haven’t kept up with this new reality, Hammond and other experts told Vox, even in states where marijuana is legal. That’s why experts increasingly view the outbreak as evidence in the case for decriminalizing marijuana at the federal level. States haven’t been able to protect the public from dangerous vape products, and so it may be time for agencies experienced in regulating consumer products, like food and drugs, to take over, they say.

To understand why, let’s take a closer look at the black market for THC vape products and its role in vaping-related lung disease.

What are black market THC vape products and what do we know about them?

A quick tour of the basics of black market THC vape products: Vape devices, also known as e-cigarettes, are battery-powered gadgets that deliver nicotine or flavors through an aerosol. They do this by heating a solution of colorless solvents (most commonly propylene glycol and vegetable glycerin) and other additives. When people vape THC, the solution also contains THC oil. (Note the difference here from smoking a joint or using a dried herb vaporizer.)

There are a variety of devices that aerosolize THC liquids. But the most common, according to the Wisconsin and Illinois data, are vape pens that take pre-filled cartridges, and tank-based devices, that can be filled with THC-containing liquid. The cartridges or liquids that go into the devices can be purchased from authorized stores in states like Colorado that have legalized marijuana products or from unauthorized, black market sources, such as dealers or online shops. (In states that haven’t legalized marijuana, all sources are considered black market. But states with legal markets also have black markets — more on that later.)

We don’t have a lot of information about the black market for cannabis products. “It is somewhat shocking how little we know,” said Hammond. And that’s the nature of black markets: They are, by definition, murky and hard to track — and the one for pre-filled vape cartridges is also relatively new.

Here’s what we do know: In 2016, the overall market for cannabis in the US — from both licensed and unlicensed sources — was estimated at $50 billion. An analysis by RAND found the fastest growing segment of the state-legal cannabis market in Washington state (one of the first to legalize recreational marijuana) was “extracts for inhalation”, which includes vape pens and cartridges.

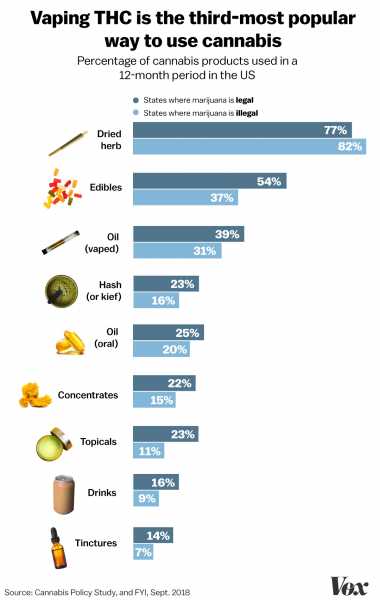

The International Cannabis Policy Study, which surveyed 30,000 people in September 2018, uncovered a similar trend: While dried herb remains popular, more than 30 percent of users report vaping THC oil. Many others are using edibles and concentrates (cannabis that’s been processed to increase its potency).

Notably, the processed THC products are more potent than dried herb. Dried herb typically contains 10 to 20 percent THC. THC vape oils can contain much more. “[They] typically have 70 to 90 percent THC,” Hammond said, based on his past and forthcoming studies, “and can contain as much as 99 percent THC.”

How these products might be sickening people

Federal health officials and investigators haven’t pinpointed a specific product or ingredient that’s at fault, and not all the patients in this outbreak reported using THC products. (In every study, there’s a subset of people who say they only vaped nicotine, for example.)

But investigators do have some ideas about what could be happening with the cases involving THC. Since THC cartridges seem to be an issue, it’s possible some ingredient has been introduced into the US supply chain that’s sickening people. (And considering no other country is experiencing a similar outbreak of this scale, and that millions of people have used nicotine e-cigarettes over many years without an apparent problem like this so far, the contaminant theory makes sense.)

One potential contaminant is vitamin E acetate. Of the 225 THC-containing products FDA has tested, as of October 11, 47 percent contained the oily substance. The new Utah data found the chemical in 89 percent of the THC-containing cartridges tested there. New York state also found vitamin E acetate in many of the cartridges respiratory illness patients had used. Even though vitamin E acetate is safely used in nutritional supplements, it isn’t safe to inhale into the lungs.

It’s also possible that another, yet-to-be-identified ingredient is making people sick. “[Black market products can] include other chemicals,” such as pesticides, said Beau Kilmer, director, RAND Drug Policy Research Center. “And as we’re seeing [with the outbreak], some of those chemicals can be very harmful when vaporized.”

Why current cannabis safety regulations aren’t strong enough

Because marijuana is still illegal at the federal level, it’s up to states in places that have legalized to regulate their markets. And the outbreak is showing that this approach isn’t doing enough to keep consumers safe, Scott Gottlieb, the former head of FDA, argued in the Wall Street Journal recently:

Indeed, cannabis health regulations vary widely among the states, Leo Beletsky, professor of law and health sciences at Northwestern University, told Vox, and they’re generally insufficient.

So in Washington, for example, the Liquor and Cannabis Board regulates the recreational cannabis marketplace, and products are tested for “potency, moisture, foreign matter, microbiological, mycotoxins (fungi), and residual solvents,” according to a spokesperson there. Medical grade products are also tested for pesticides and heavy metals.

In California, products are third-party tested for the same kinds of contaminants Washington looks for, and the state Department of Health’s regulations for cannabis requires “manufacturers to utilize good manufacturing practices in the production of cannabis products,” a spokesperson there said, including listing all ingredients on the label.

But states typically don’t require manufacturers to submit safety data before marketing their products, nor do they conduct random spot checking of cannabis products to make sure that what manufacturers claim about their products is true.

“How confident [are state regulators] that some of the ingredients used in vape oils are safe? I don’t know if anyone knows that.”

Their list of tests also doesn’t include checking for chemicals, such as vitamin E acetate, that are emerging as a health threat. “Until only recently with the outbreak of the vapor associated lung injury crisis, no one suspected additional safety tests should be considered,” the Washington spokesperson said.

On top of that, there’s just a lot we don’t know about the health impact of vaping THC oil. “How confident [are state regulators] that some of the ingredients used in vape oils are safe?” Hammond said. “I don’t know if anyone knows that. It’s the manufacturer’s job to make sure products don’t include harmful chemicals. But the whole concept of vaping from liquids is fairly new and we don’t have a lot of certainty.”

Why federal decriminalization could help

Legalizing cannabis products at the federal level would mean developing a regulatory framework that’s likely to be more stringent, Beletsky argued. “What federal legalization would do is allow for a more uniform and predictable and clear set of rules that would draw on the experience and expertise of the federal agencies in regulating consumer markets.”

In other words, federal officials at agencies like the FDA should pursue what they already know works in consumer protection for other products: premarket regulation, inspection, and spot-checking to make sure people follow the rules. “It’s not rocket science,” Beletsky said. “We wouldn’t be inventing something from scratch but borrowing from other [federal] regulations.” (For more on the cases for and against legalization, check out German Lopez’s reporting.)

There’s another thing the current piecemeal approach to legalization has done, which federal regulation could help: It spurred on a black market to fill the gaps in demand for THC vapes.

In states that haven’t legalized cannabis, black market products are all that’s available. But even states that have legalized the drug struggle to contain existing black markets, Rand’s Kilmer explained. “The size of the illicit cannabis market is largely a function of the prices in the legal market, availability of legal outlets, and resources dedicated to enforcing the law against unlicensed producers,” he said.

So sometimes black market products are simply cheaper or easier to access than legal products. Consumers may also prefer whatever their dealer is selling.

If marijuana were legal across the country, though, access and price barriers would likely improve as a workable retail systems get up and running, Hammond said. “I would expect legal markets to solve the [black market] problem, but I would expect product standards to help reduce the problem, especially if consumers now have a greater incentive to avoid illicit products.”

Listen to Today, Explained

Will vaping kill you? Maybe.

Looking for a quick way to keep up with the never-ending news cycle? Host Sean Rameswaram will guide you through the most important stories at the end of each day.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Sourse: vox.com