Black Voices for Trump launched earlier this month with a splashy event at the Georgia World Congress Center featuring HUD Secretary Ben Carson, pizza impresario Herman Cain, social media personalities (whatever that means) Diamond & Silk, and President Trump himself, who vowed “to campaign for every last African-American vote in 2020.”

Republicans have struggled with black voters for generations now. And given Trump’s well-documented history of racism, he seems like an awfully unlikely leader to turn the trend around. So much so that the event was largely noted in progressive circles for the fact that some of the attendees decked out in MAGA gear were, in fact, white.

Peter Baker, doing news analysis for the New York Times, tried to make sense of the whole thing by positing that the outreach “appeared aimed at reassuring suburban white voters discomfited by his use of racist tropes and incendiary language” rather than being an actual effort to “expand the president’s meager support among African-Americans.”

But even though Trump’s outreach to black voters is overwhelmingly tacky and ridiculous, it shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand. After all, Trump’s courting of white working-class voters is tacky and ridiculous, but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t work.

Even a very successful outreach, though, will still leave Trump losing badly among black voters, who overwhelmingly do not support him. But it also means that Trump’s got nowhere to go but up. And the bulk of the evidence suggests that support among black voters has in fact gone up and may rise even further depending on how the rest of the 2020 cycle plays out.

Democrats have been slipping with black voters

It’s well established that African American turnout declined in 2016 to the levels seen in pre-Obama elections, even as turnout rose in other demographic categories.

Less known, as Philip Bump wrote last year, is that Trump actually “did slightly better with black voters than did John McCain in 2008 or Mitt Romney in 2012,” albeit worse than George W. Bush or earlier Republicans.

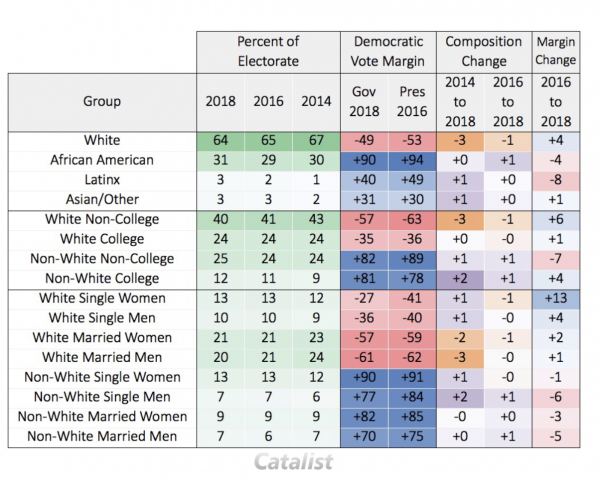

More interesting is that the slippage in vote choice continued through to the 2018 midterms. Turnout wasn’t the issue here, with African Americans constituting 12 percent of the midterm electorate, flat from 2016 and the highest-ever recorded for a midterm. Rather, according to Democratic data firm Catalyst’s analysis of the results, Democrats won the black vote by “only” a 90 percentage point margin in 2018 House races down from 93 percent in the 2016 presidential.

Obviously that’s still a huge landslide. But the direction of the shift is striking. House Democrats in 2018 did 7 percentage points better than Hillary Clinton with non-college whites and 10 percentage points better with white college grads on the path to a popular vote edge of 7 percentage points rather than 2.

A similar pattern is observable in specific key races. In Georgia, for example, Stacy Abrams’s much-touted efforts to increase minority turnout were largely successful and the electorate was less white than the state saw in 2016 or 2014. But in terms of voters’ choices, Abrams did better than Clinton with Georgia’s white population but worse with black voters.

In Minnesota, which featured two separate Senate races, the two Democratic candidates ran 22 points ahead of Clinton with non-college white voters, 28 points ahead of her with white college graduates, and two points weaker with non-college non-whites.

In other words, while Republicans remain deeply unpopular with non-white voters, the clear backlash against Trump-era Republican governance was an exclusively white phenomenon. And there are some real indications that Trump has managed to personally hold on to these gains.

Trump seems to have gotten slightly more popular with black voters

One piece of evidence is right there in Baker’s skeptical write-up of Trump’s outreach efforts.

“Trump received about 8 percent of the black vote in 2016,” Baker writes, “and has an approval rating of about 10 percent among African-Americans.”

Ten percent is a low approval rating, but 10 is a bigger number than 8. Given that back in 2016, Trump won a non-trivial number of votes from people who didn’t approve of him, those numbers are perfectly consistent with a story in which Trump has picked up 2-3 percentage points worth of black support.

A recent rigorous poll of the main swing states conducted by Sienna College and the New York Times indicated that he might be doing even better than that. Testing Trump head to head against Joe Biden, Elizabeth Warren, and Bernie Sanders, the poll showed all three Democrats even or ahead of Clinton with white voters but distinctly behind with black ones.

Warren and Sanders almost certainly have an opportunity to improve their numbers here by becoming better known and consolidating baseline party support if they become the nominee. But Biden is not suffering from a lack of name recognition; he’s clearly the most popular Democrat in the field with black voters. And of course his 74-point edge over Trump is massive, it’s just smaller than Clinton’s edge — another sign that Trump has made modest inroads with the demographic.

Marginal voters aren’t average voters

Not everyone is buying it, of course.

Cornell Belcher, a pollster and political consultant with expertise in racial issues, tells me the signs of a bump in Trump support are “statistical noise” and “he isn’t picking up ground anywhere.”

And indeed while one reaction to the Sienna polls showing an ultra-tight race in the swing states has been to intensify Democratic hand-wringing about electability, more optimistic Democrats cite this data to make the exact opposite point — that to carry the pivotal states requires Trump to make implausible gains with black voters.

But the 2018 results are telling in this regard. It’s hard to say exactly why Abrams ran 4 points weaker than Clinton with black voters, but if she’d equalled the result of two years earlier she’d likely have won the election — and if black voters had swung against the GOP to the extent that white ones did, she definitely would have won. Nobody would consider her opponent Brian Kemp’s campaign to have been a triumph of African American outreach by any means, any more than losing among black voters by a 74 percent margin to Joe Biden would mean that Trump is popular among black voters.

Small changes, however, make a big difference in close elections. And the critical point is that precisely because Republicans are so weak with black voters, the views of marginal black voters may be very different from the views of average ones. So Trump’s gimmicky and somewhat ridiculous outreach can be effective, even if it’s rejected by the vast majority of the target audience.

Meanwhile, it really is true that Trump signed a significant criminal justice reform bill and that under Trump the black unemployment rate has reached a record low — as has the gap between the black and white unemployment rates. Trump obviously isn’t going to break African Americans’ support for the Democratic Party. But it’s hardly inconceivable that he could gain some votes. The most likely explanation for his black outreach efforts is the simplest one: The team sees an opportunity, and they’re trying to seize it.

Sourse: vox.com